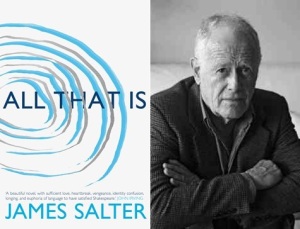

James Salter is one of few modern writers able to create equally compelling male and female characters. He says it’s because he has made a conscious “effort to nurture the feminine” in himself and in his responses to the world around him which “pure masculinity” often discounts. This very shrewdly cultivated skill is something one can clearly see in All That Is, rippling with atmospheric vitality and meticulously developed men and women vying for the reader’s attention. The story of Salter’s first novel in over 30 years revolves around former naval officer, now book editor, Philip Bowman and the people who drift in and out of his life. The book itself is primarily concerned with the nature of love, the hardship of relationships and the way in which people deal with both. After returning home from Okinawa and a stint at Harvard, Bowman meets and falls for a young woman by the name of Vivian Amussen. “He saw himself tumbled with her among the bedclothes and fragrance of married life,” Salter writes of Bowman’s daydreams, “the meals and holidays of it, the shared rooms, the glimpses of her half-dressed, her blondness, the pale hair where her legs met, the sexual riches that would be there forever.” Shortly after the couple tie the knot, however, Bowman learns that nothing lasts forever, especially marriage. Theirs sours rapidly as Vivian loses interested in her husband’s bookish whimsies, in his talk of high culture and his quixotic reveries.

With his marriage over, Bowman travels to London on business where he meets Enid Armour – a sultry South African English blonde with a chronic philanderer for a husband. The pair embark on an affair and following Bowman’s divorce travel to Spain to consummate their romance, to consolidate their fledgling love. It is here in his descriptions of cities and their poetry through the eyes of the lovers that Salter reveals himself to be a master of etymology and lyrical precision. His rolling sentences flow mellifluously from one page to the next, creating iridescent snapshots of García Lorca’s homeland, effortlessly integrating his story and the country’s history into the narrative. “He was…an angel of the re-awakening of Spain in the 1920s and ‘30s,” Slater writes, “[his] books and plays filled with a pure, fatal music, and poems rich in colors with fierce emotion and despairing love.” Numerous historical elements and literary references are interwoven into the plot, adding to the wonderfully rich tapestry of Salter’s prose. Salter captures the glamorous milieu of Europe – Greece, France, Spain – in all its glory, through opulent literary ruminations over its present and its past. He goes from describing places to describing people in them with graceful fluency, connecting the two to create a larger, more vivid picture. “They went to Toledo for a day and then on to Seville, where summer lingered and the voice of the city, as the poet said, brought tears,” he writes of the two lovers in Spain, “They walked through walled alleyways, she in high heels, bare-shouldered, and sat in the silent darkness as deep chords of a guitar slowly began and the air itself stilled.”

This kind of tender evocation also extends to Salter’s images of the lovers in their most intimate moments. “The glory of her,” Bowman marvells looking at Enid, “England stood before him, naked in the darkness…He pulled her over him by her wrists, like a torn sheet.” But for all their passion, Bowman’s relationship with Enid eventually fizzles out and the two part. Shortly after, he meets Christine Vassilaros and her young daughter. The pair fall in love and set up house, living in blissful domesticity or so Bowman thinks until one day Christine decides it’s over. Inexperienced, uncertain and self-doubting Bowman appears to be the very antithesis of a romantic lead and in many ways remains so until the end. He laments his incompetence with women from the start, blaming it on his absent father. There are nebulous questions over Bowman’s masculinity and there is but one moment in the book when he exercises its full force, revealing the truly chilling side of man. Wounded by Christine’s betrayal and humiliated by having to forgo the house they shared Bowman waits patiently to take his revenge, which comes as an unexpected twist in the otherwise linear plot. Salter brings the story to an equally unexpected close, which in many ways reflects the precariousness of life. “He had been married, once, wholeheartedly and been mistaken,” Salter writes of Bowman toward the end of the book‚ “He had fallen wildly in love with a woman in London, and it had somehow faded away. As if by fate one night in the most romantic encounter of his life he had met a woman and been betrayed. He believed in love – all his life he had – but now it was likely to be too late”. This rather reductive view is relegated by Bowman himself just pages later as he realises that it is, in fact, never too.

All That Is is a lyrical meditation on the human condition, replete with languorously poetic turns cut with fastidious precision. The book’s key themes evoke universal interconnections, between love and death, loneliness and companionship drawing the conclusion that one’s fate depends almost entirely upon oneself. Yet the book is much more than a romantic allegory, All That Is also deals with a number of other topics such as identity, social exclusion and inclusive alienation. The latter are diligently rooted in the plot. Bowman feels an outsider, an interloper at Harvard and a stranger in his American-Jewish social circles despite being inexorably linked to his friends and acquaintances by a shared cultural heritage. Bowman is the vessel through which Slater channels the search for one’s identity, in and out of relationships. And in this Bowman is uncompromising, refusing to settle into a cosy existence by way marriage, electing to teeter on the peripheries of the in-crowd. “He might have married one [a Jewish woman] and become part of that world, slowly being accepted into it like a convert,” Salter writes of Bowman’s decision, “He might have lived among them in that practical family density that had been formed by the ages, been a familiar presence at seder tables, birthday gathering, funerals, wearing a hat and throwing a handful of earth into the grave. He felt some regret at not having done it, of not having had the chance. On the other hand, he could not really imagine it. He would never have belonged.”

This sense of otherness is a motif throughout the book. Bowman’s search for a place in the world is defined by his romantic failures, which continuously distort and destabilise his sense of self until he finds love once again. All That Is is characterised by Salter’s trademarks, his geometric prose, his tacit force, decisive authority and erotic realism. Sex lends the book much of its thematic unity both individually and in relation to Salter’s other works. On occasion, the amorous liaisons lack the poetry of the more commonplace scenes but Salter redeems himself through those. Speaking in a recent interview, the writer said that he “will never again write a book in which there’s a single sexual act”. This might prove to be an interesting exercise if, indeed, Salter decides to write another book. Certainly, his “energy and desire” seem to be intact as is his lifelong passion for flying. Like his protagonist, Salter was a military man, a US air force pilot, who gave it up to pursue a career in the literary world. This inevitably invites one to draw comparisons between the two men, but while Bowman often appears finite and fallible Salter does not. He commands attention with the inimitable certainty of a master storyteller, a literary frotteur, a man who likes to “rub words in his hand” but one who never minces them.

The Paris Review | James Salter

Guardian | James Salter

Publisher: Picador

Publication Date: May 2013

Hardback: 304 pages

ISBN: 978-1447238249