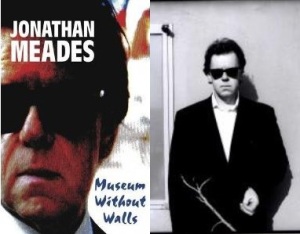

Jonathan Meades: An indefatigable deipnosophist and a polyhistor

“There is no such thing as a boring place,” says Jonathan Meades. And let’s face it, he should know having spent a lifetime “writing about it in different media and in different ways: polemically, analytically, essayistically, fictively”. Place, albeit not exclusively or singularly, is also the subject of his new collection, Museum Without Walls. The sturdy hardback – boasting 54 prose pieces and six film scripts – delivers some genuinely droll and outré views and ideas, all backed up by an astonishing wealth of knowledge. Meades is an indefatigable deipnosophist and a polyhistor, who often veers off course to fascinating ends. Writing about architecture, for example, in Hamas & Kibbutz he deviates from the topic at hand to the subject of football, pondering: “If it is a national game how come we always lose?” He writes more amusingly, however, about one of the game’s biggest stars, saying: “A buzzard is an avian analogue of the even squeakier David Beckham,” who will “always be a wrong voice, a treble in a tenor’s body. That for me is his defining characteristic. He is to be filed, ultimately, alongside Alan Ball and Emlyn Hughes in the Sportsmen Posing As Castrati category”. Yet jocund badinage aside, Meades really knows his stuff from seventeenth century literary dicta to the ineptitude of an untutored architect, from the demerits of the Theory of the Value of Ruins to the capital’s imperfect traffic and transport systems. Meades is a redoubtable social critic and nouveau historian with an intrepidly facetious streak, humorous and clever without being glib.

Much of Museum Without Walls is dedicated to Meades’ monomania, which he has spent 30 years cultivating in numerous television programmes, books and journalism features. Here, in this collection, are some of his most interesting texts pertaining to London and its monuments, both the memorable and the unremarkable. “Of London’s major set pieces,” writes Meades, “St Paul’s Cathedral is the most distinguished, though not, I suspect, the most loved: it is too stately, aloof and worldly to excite the sort of affection granted to such exercises in quaintness as Big Ben and Tower Bridge”. Further in the collection Meades ruminates over the subject again, praising St Paul’s for its “swagger and urbanity and temporal grace,” which stands at odds with its function as a church, “a monument to unreason…a musty repository of ancient mysteries and incomprehensible superstitions” and the residence of “the fearsome, jealous, tyrannical wrath-monger called god”. Meades continues his deadpan fulmination against the numinous deity in the brilliantly irreverent Absentee Landlord. God is “an absurdity whose existence it is absurd to deny,” he says, “because God is omnipresent, God is in believers’ minds or souls or hearts or wherever it is they know he is”. In fact, he is a “fantastically successful invention.” And if an idea ever had legs Meades muses, “this one has run and run and is still full of puff”.

Next, he tackles the church. The Church of England to be precise or rather “the Church of Convenience,” as he calls it, “founded to sanction a king’s polygamous lubricity and his Bluebeard appetites”. Speaking from an architectural point of view, however, he avers that churches as buildings cannot be denied. Most of these putatively sacred structures are lumped together as Gothic, because they predominantly are and have been since the Middle Ages. “The Gothic is an agent of de-secularisation, it is an architectural means of achieving sacredness,” Meades explains, “it made schools, law courts and railway stations into quasi-religious building which were thus invested with added authority: we thanked God for selective education, for the wisdom of judges, for making the trains run on time.” Interestingly, Meades goes on to note that “Atheism, unlike Christianity, possesses no architectural type or decorative style which is peculiar to it.” And yet he daydreams here a little, saying: “Still, had atheists built they could have built at no more propitious a moment than during the middle years of this century, when nearly all architecture had broken with western Christian precedent, when architecture was so ideologically determined that it was itself a cult or religion.” Sadly this is no longer the case, as Meades laments in Postmodernism to Ghost-Modernism because modern British architecture died when Margaret Thatcher assumed power in 1979 and thus dismantled the “economic and cultural apparatus that had supported it”.

And, it only got worse under the tenure of Tony Blair, “the most bellicose prime minister of the last 150 years”. There is something of the Uriah Heep that Blair’s “corrupt regime” has banqueted to Britain, says Meades. But what he really takes objection to are the “block upon block of luxury flats” despoiling different cityscapes across the country. In On the Bandwagon talking of Blair’s government, Meades says that the decade-long rule “will be recalled as much by its architecture as by its low dishonesty”. But the architectural legacy is Meades’ primary concern, so much so that he has coined a neologism for the particular type of structure associated with New Labour. A sightbite, the analogous equivalent of a soundbite, is “characterised by its hollow vacuity, by its sculptural sensationalism, by its happy quasi-modernism, by its lack of actual utility”. These “dangerously vapid” buildings found mostly in municipalities undergoing regeneration, from London’s Docklands to Cardiff Bay, are fully representative of the government who authorised them. A government this particular auteur takes to task where others have not dared. Meades’ spellbinding enthusiasm, his acuity and his crafty prose in writing about social, political and religious issues – which he contemplates with wit, deft and gravity, depending on the exact nature of the topic – are surpassed only by his uncompromising candour.

This candour also extends to his life, his childhood and formative years, references and anecdotes of which punctuate the collection. Occasionally, these sketches are plaintively nostalgic as those, for example, in Fatherland, where Meades remembers places associated with his father, which he says “coalesce into a memento mori whether I like it or not”. Thus places, like certain smells and sounds, are able to solicit small and inconsequential but also exigent and momentous reminiscences and are therefore an integral element of our emotional life. A great number of these places for Meades are – in a very quintessentially English way – pubs, or more precisely their parking lots, where he whiled away the hours eating crisps and imbibing fizzy lemonade, waiting for the grown-ups. “I spent the 1950s in pub car parks,” he confesses, “in summer I kicked gravel, walked perilously on the wall tops, scaled trees. In winter which is what it usually was I sat in my father’s car watching my breath condense, mining driving, scrutinising the underside of Issigonis’s dashboards, reading maps”. Here like elsewhere in the collection Meades pays tribute to his father, a biscuit salesman with whom he travelled from town to town, taking-in the beautiful, the grotesque and the commonplace which, in his own words, grew to seem extraordinary. Unbeknown to young Meades at the time his edacious interest in his surroundings would not only develop into a lifelong fascination but also into a brilliant career, both in print and in television. The six scripts gathered here give unprecedented insight into the filmmaker’s pedantic precision and attention to detail. Surprisingly – surprisingly because Meades’ television programmes appear so wonderfully spontaneous – every nuance and scene, every screen-shot and take is meticulously scripted, attesting to Meades’ proficient showmanship. Just as Museum Without Walls attests to his talents as a writer with an exciting and varied body of work of which one hopes there is much more to come.

Publisher: Unbound

Publication Date: September 2012

Hardback: 352 pages

ISBN: 9781908717184