J.D. Salinger: Unmatched, unparalleled and, in fact, inimitable

Sitting anxiously on an unwieldy polypropylene chair and perusing one of those consummately moronic-fashion magazines to pass the time while waiting to be called in for my 5:45 appointment, I snarled and fawned at numerous depictions of girls lacking any vestige of verisimilitude. Eventually, benumbed by the thought of having to read a feature on how to make your own four-tier wedding cake, I plucked a book of short stories from my bag and began reading A Perfect Day for Bananafish. Funnily enough, the story opens with a girl in a hotel room reading an article in a “pocket-sized women’s magazine” called “Sex is fun – or Hell,” while waiting for a long-distance phone call. The similarity was completely coincidental, but truth be known I would have rather read the aforementioned feature than one on baking. I fear it is a little too late for my culinary erudition.

News of J.D. Salinger’s death, on 27th January 2010, came as unexpectedly as the ending in A Perfect Day for Bananafish. I cried – suddenly, childishly – assailed by brackish melancholy and funerary newsprint; and later, spent the evening looking for answers at the bottom of a vodka glass. A somewhat ridiculous reaction perhaps but one of spontaneity rather than premeditation. My interest in books began at the age of 12 with the reading of The Catcher in the Rye. I read it many times thereafter and a lot of books since, including all of Salinger’s, but now looking back I think it was that particular book and that particular writer who singlehandedly shaped my reading preferences and thus his death was like a dissolution of a part of my own childhood. There are many reasons why I love Salinger, some obvious, others not, but one of them is captured perfectly in the following snapshot: when Elia Kazan asked Salinger’s permission to produce The Catcher in the Rye on Broadway, Salinger simply replied: “I cannot give my permission. I fear Holden wouldn’t like it.” And for that, and all his marvellous prose, Salinger will always be, for me at least, unmatched, unparalleled and, in fact, inimitable.

The first part of A Perfect Day for Bananafish takes place in a room at a Florida hotel full of “New York advertising men…monopolising the long distance lines”. The girl waiting to receive a call is the sort who wears elegant Saks blouses, varnishes her nails in classic-scarlet red and looks “as if her phone had been ringing continually ever since she reached puberty.” Muriel eventually picks up the phone, after the fifth or the sixth ring, while nonchalantly passing her freshly lacquered left hand “back and forth through the air” to be greeted with her mother’s concerned: “I’ve been worried to death about you.” As the conversation progresses the reader is introduced to a character initially known as “he” who emerges as a somewhat facinorous personage or at least one whose peculiar behaviour and “funny business with trees” makes him sound unhinged. The “he” in question is Muriel’s husband, Seymour Glass, fresh off the boat from a battlefield in Germany and deeply troubled by the horrors he witnessed in the trenches. His wife, “Miss Spiritual Tramp of 1948” as he calls her, is oblivious to her husband’s plight or anything beyond her insular world of conservative Manhattan. Muriel is bovaristic, conceited and superficial, even in her conversation with her mother which shifts without preamble from “her raving maniac” husband and the merits of psychoanalysis to her “blue coat” which too isn’t perfect and needs alterations. Salinger juxtaposes the subjects, the shallow with the weighty, to highlight the inanity of the former and the general lack of understanding about the latter. A Perfect Day for Bananafish centres around the after-effects of war, and the invisible wounds it leaves on those who have been privy to its monstrosities.

The subject matter is close to Salinger’s heart, and one he experienced first-hand while serving as a sergeant during World War II. Salinger landed on Utah Beach, Normandy, France, on D-Day in 1944 to fight against the Germans and spent the next year in battle, once writing to his mentor and Story magazine editor Whit Burnett to say he was unable to “describe the events” he had seen because they were too “horrendous to put into words.” The initial sights of war, the burning machine guns, wounded soldiers slipping away of exsanguination, crashing mortars, and fatal ambushes, remained with Salinger for the rest of his life. He never spoke about them, like Seymour, but they were said to have entrenched themselves on his memory. Seymour is in many ways a doppelganger of Salinger, endowed with the exact same feelings and post-traumatic stress symptoms that Salinger himself experienced.

Salinger’s foray into writing began in the Spring of 1939 when he audited a Friday evening short-story writing class at Columbia University given by Burnett, who later remembered Salinger as a quiet young man who sat in class “without taking notes, seemingly not listening, looking out the window.” Salinger daydreamed through the course then much to everyone’s surprise wrote a brilliant short story called The Young Folks which Burnett published in Story magazine in 1940. Salinger continued writing throughout his time in service, on a portable typewriter which he kept in his Jeep. The stories written during this time were published in various popular magazines such as the Saturday Evening Post and Esquire, and depicted the subject of war. Later, Salinger refused to have the stories reprinted simply saying he didn’t “think they were worthy of publishing.”

Like Seymour, Salinger wrangled with “battle fatigue” and a sense of loneliness, isolation, ineffectuality and feelings of being a misfit long after he returned from the war. A Perfect Day for Bananafish is an implicit nod to Salinger’s own internal turmoil, a cathartic exercise to relay the largely undisclosed and ongoing tumult of a soldier off the battlefield. In a bid to steady his life, Salinger sought to get married and did so in 1945 to a woman of German extraction called Sylvia, with characteristically teutonic features, pale skin, and who, like Muriel, habitually sported “blood red lips and nails”. The couple’s relationship was “extremely intense both physically and emotionally” with Salinger once claiming that she had “bewitched him”. Sylvia filed for a divorce on 13th June 1946, and the two never saw each other again. He continued to write without much acclaim or success, until in 1948, after a decade of rejection slips, the New Yorker published A Perfect Day for Bananafish which kick-started his career as a serious writer. The second part of the story takes place on the beach outside the Florida hotel where a sprightly little girl, by the name of Sybil approaches a young man decubitus on the sand in his “terry cloth robe”.

The story’s main motif formulates in the latter part when Seymour is confronted with the innocence of a child who becomes an unwitting catalyst for the way he chooses to deal with his affliction, having quietly realised that his own innocence is irretrievably gone. And yet Seymour is momentarily drawn in to the little girl’s world, its childish fancies and naive whims, when he suggests the two go catch a “bananafish.” The little girl doesn’t question his yarn, but rather sets of on the adventure holding Seymour’s hand while he tells her about “bananafish” saying: “They lead a very tragic life. You know what they do Sybil? Well, they swim into a hole where there’s a lot of bananas. They’re very ordinary-looking fish when they swim in. But once they get in they behave like pigs. Why, I’ve known some bananafish to swim into a banana hole and eat as many as 78 bananas…Naturally, after that they’re so fat they can’t get out of the hole…They die.” The thought of death, brings Seymour back to the present prompting him to stop abruptly and say “We’re going in now,” before kissing Sybil goodbye. A sense of sadness underlines the pathos of Seymour’s predicament, and yet while the exchange between him and the girl seems entirely care-free a sense of foreboding is never far away. The story ends back in hotel room 507, redolent “of new calfskin luggage and nail lacquer remover,” with a closing that shocks me to this day. Re-reading the story, and thereafter contemplating the most recent and bloody world conflicts and all the lives they’ve claimed, I realised that the old lie: “Dulce et Decorum est Pro patria mori,” has never seemed so old, devious or prevaricating as it does today.

RIP Sam.

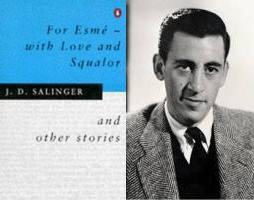

[A Perfect Day for Bananafish is the first story in the For For Esmé – with Love and Squalor collection.]